This story was published the day after the experiment ended.

(Click the image to open it. Scroll down for the transcribed text)

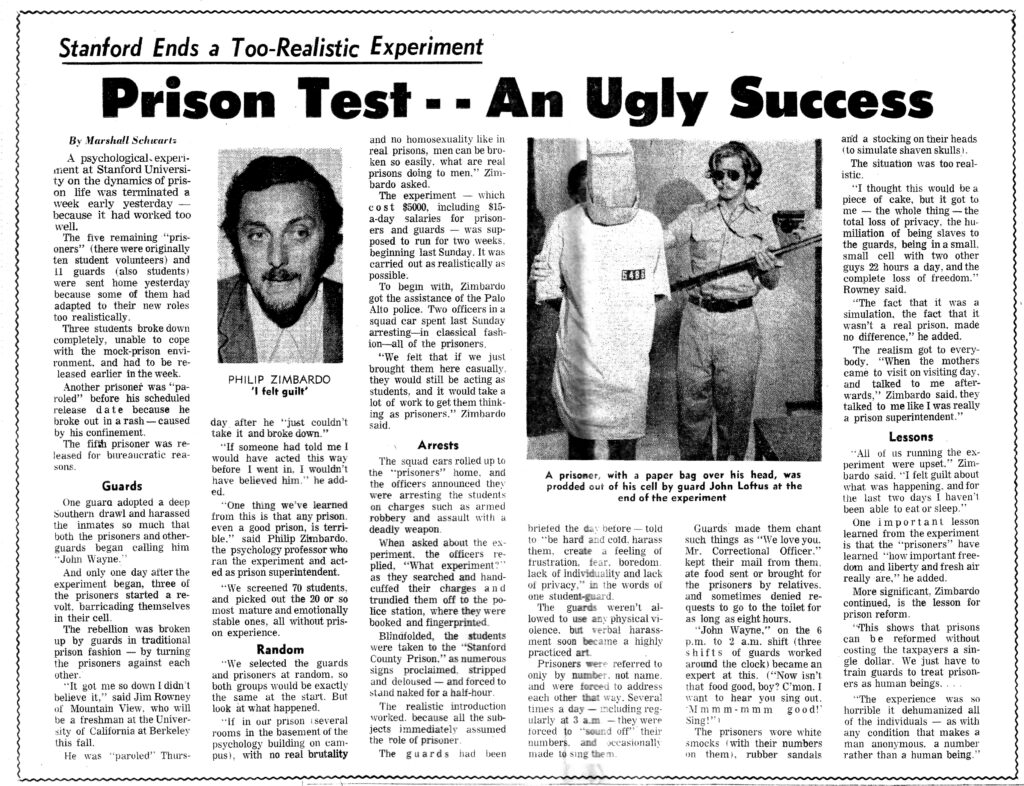

Photo 2: “A prisoner with a paper bag over his head was prodded out of his cell by guard John Loftus at the end of the experiment.”

Stanford ends a too-realistic experiment. Prison Test — An Ugly Success

by Marshall Schwartz.

A psychological experiment at Stanford University on the dynamics of prison life was terminated a week early yesterday because it had worked too well. The five remaining prisoners, there were originally ten student volunteers, and eleven guards, also students, were sent home yesterday because some of them had adapted to their new rules too realistically. Three students broke down completely, unable to cope with the mock prison environment, and had to be released earlier in the week. Another prisoner was paroled before his scheduled release date because he broke out in a rash caused by his confinement. The fifth prisoner was released for bureaucratic reasons.

GUARDS

One guard adopted a deep southern drawl and harassed the inmates so much that both the prisoners and other guards began calling him John Wayne. And only one day after the experiment began, three of the prisoners started a revolt, barricading themselves in their cell. The rebellion was broken up by guards in traditional prison fashion by turning the prisoners against each other. “It got me so down I didn’t believe it,” said Jim Rowney of Mountain View, who will be a freshman at the University of California at Berkeley this fall. He was paroled Thursday after he just couldn’t take it and broke down. “If someone had told me I would have acted this way before I went in, I wouldn’t have believed him,” he added. “One thing we’ve learned from this is that any prison, even a good prison, is terrible,” said Philip Zimbardo, the psychology professor who ran the experiment and acted as prison superintendent. “We screened 70 students and picked out the 20 or so most mature and emotionally stable ones, all without prison experience.”

RANDOM

“We selected the guards and prisoners at random, so both groups would be exactly the same at the start. But look at what happened. If in our prison several rooms in the basement of the psychology building on campus, with no real brutality and no homosexuality like in real prisons, men can be broken so easily. What are real prisons doing to men?” Zimbardo asked. The experiment, which cost $5,000, including $15 a day salaries for prisoners and guards, was supposed to run for two weeks beginning last Sunday. It was carried out as realistically as possible. To begin with, Zimbardo got the assistance of the Palo Alto police. Two officers in a squad car spent last Sunday arresting, in a classical fashion, all of the prisoners. “We felt that if we just brought them here casually, they would still be acting as students, and it would take a lot of work to get them into thinking as prisoners,” Zimbardo said.

ARRESTS

The squad cars rolled up to the prisoner’s home and the officers announced they were arresting the students on charges, such as armed robbery and assault with a deadly weapon. When asked about the experiment, the officers replied, “What experiment?” as they searched and handcuffed their charges and trundled them off to the police station, where they were booked and fingerprinted. Blindfolded, the students were taken to the Stanford County Prison, as numerous signs proclaimed, stripped and deloused, and forced to stand naked for a half hour. The realistic introduction worked because all the subjects immediately assumed the role of prisoner. The guards had been briefed the day before. Told to be hard and cold, harass them. Create a feeling of frustration, fear, boredom, lack of individuality, and lack of privacy, in the words of one student guard. The guards weren’t allowed to use any physical violence, but verbal harassment soon became a highly practiced art. Prisoners were referred to only by number, not name, and were forced to address each other that way. Several times a day, including regularly at 3 a.m., they were forced to sound off their numbers and occasionally made to sing them. Guards made them chant such things as, “We love you, Mr. Correctional Officer.” Kept their mail from them, ate food sent or brought for the prisoners by relatives, and sometimes denied requests to go to the toilet for as long as eight hours. John Wayne, on the 6 p.m. to 2 a.m. shift, three shifts of guards worked around the clock, became an expert at this. “Now isn’t that food good boy? Come on. I want to hear you sing out.” “Mmm, good. Sing.” The prisoners wore white smocks with their numbers on them, rubber sandals with a stocking on their heads to simulate shaved skulls. The situation was too realistic. I thought this would be a piece of cake, but it got to me, the whole thing. The total loss of privacy, the humiliation of being slaves to the guards, being in a small, small sale with two other guys, 22 hours a day, and the complete loss of freedom, Rowney said. The fact that it was a simulation, the fact that it wasn’t a real prison, made no difference, he added. The realism got to everybody when the mothers came to visit on visiting day and talked to me afterwards, Zimbardo said. They talked to me like I was really a prison superintendent.

LESSONS

“All of us running the experiment were upset,” Zimbardo said. “I felt guilt about what was happening, and for the last two days I haven’t been able to eat or sleep.” One important lesson learned from the experiment is that the prisoners have learned how important freedom and liberty and fresh air really are, he added. “More significant,” Zimbardo continued, “is the lesson for prison reform. This shows that prisons can be reformed without costing the taxpayers a single dollar. We just have to train guards to treat prisoners as human beings.” The experience was so horrible it dehumanized all of the individuals, as with any condition that makes a man anonymous a number rather than a human being. Photo caption. A prisoner with a paper bag over his head was prodded out of his cell by guard John Loftus at the end of the experiment. Second photo caption. Philip Zimbardo. I felt guilt.